Pernand-Vergelesses: July 2023

We had been planning a visit to Bonneau du Martray for quite some time. This was inspired by our session with John Kongsgaard, who held the Burgundian domaine in high regard. He had visited when Jean-Charles le Bault de la Morinière was in charge. The estate changed hands in 2017, with Stanley Kroenke of Arsenal F.C. and Screaming Eagle taking ownership. Under the new general manager, Thibault Jacquet, there’s been a shift to a modern taste profile, a style that looks for the energetic power of Corton, but balanced with an electric and lively tension.

The most iconic view of the Côte d’Or is arguably the picturesque Corton hill, crowned by the historic bell tower of the Pernand-Vergelesses church. Bonneau du Martray’s vineyards are on the best lieux-dits of the hill, with the cellar right next to the church. Jacquet generously hosted us for a tour of the winery and a tasting of their two cuvées, both grand crus, a Corton-Charlemagne and a Corton Rouge.

| Table of contents | ||

| 1. The origins of the domaine | 2. A winemaking of assemblage | 3. Understanding Corton-Charlemagne |

| 4. The viticultural philosophy | 5. Élevage in many vessels and bottle ageing | 6. The tasting |

From Charlemagne to Stanley Kroenke

The domaine’s vineyards, historically significant for being once owned by Charlemagne, have a storied past. After Charlemagne, these lands were managed by the church until the French Revolution’s upheavals. Recognising the lands’ historical and agricultural potential, the Bonneau du Martray family acquired most of the Charlemagne climat after the Revolution. Although their holdings have diminished over the years, they remain one of the primary landholders in Corton, second only to the négociant Louis Latour family.

Under the le Bault de la Morinière branch of the family, the domaine would end all its leases and focus on restoring the vineyards. During the tenure of Jean-Charles le Bault de la Morinière, the last of the family line to manage the estate, transitioned to organic and biodynamic farming.

Yet, after remaining under the same family stewardship for five generations, in 2017 Stanley Kroenke, a US-based businessman with a diverse portfolio extending from sports to wine, purchased the estate. Despite this change in ownership, the core team at the domaine, with decades of experience, remained intact. The vineyard manager, Fabien Esthor, a 25-year veteran, and the winemaker, Emmanuel Hautus, with 15 years under his belt, continued their tenure.

A winemaking of assemblage in Burgundy

Interestingly, this transition brought about a newfound freedom for the team. Jean-Charles, who took over in 1994, had developed his own successful set recipe over the years. Taking the financial risk to experiment was difficult with the family-run model and even more with the low yields between the 2012 to 2016 vintages.

With the arrival of Thibault Jacquet as the general manager and more financial backing, there’s been a noticeable shift towards a more experimental, yet still cautious, approach. Jacquet, since 2017, has introduced new vessels for fermentation and élevage, selectively choosing what best enhances the wine’s quality. He was quite open about what works and what doesn’t. For example, the use of amphorae have been embraced for their ability to add purity and texture, but concrete eggs were quickly dismissed for making the wine too soft and reductive.

One of the new key strategies at the domaine under Jacquet is vinifying each of their 15 distinct plots on the Corton hill separately. Each plot has its own unique soil and microclimate, and they treat each one as its own entity. After a year, these individual wines are carefully blended to create a final product that aims to be better than the individual constituents. This approach is somewhat reminiscent of the assemblage process in Champagne, where Jacquet previously worked (he is however a Bourguignon).

Everybody that we meet tells us that we should select our favourite plot and make it. But it will never be as good as all of them combined together.

He firmly believes that through the assemblage the whole is greater than the sum of its parts. When asked about the philosophy and aim when blending the plots, Jacquet emphasizes the importance seeking not just flavor but an energy and tension that invigorates. As he puts it, a wine should be ‘alive’, offering a sensory kick akin to a morning coffee. ‘I like energy, I like precision. If the wine has big shoulders but nothing behind, it’s boring.’

If chefs can be better understood by looking at the books they have in their personal library, fro winemakers it’s what they drink. When he mentioned producers like Bachelet-Monnot and Étienne Sauzet, his keenness for tension became only clearer.

Following the acquisition in 2017, the team undertook a thorough review of their blending process. This introspection resulted in substantial changes. Blends that didn’t work or unbalanced the overall profile are sold off to a négoce. The hot, solar vintage of 2018, for instance, was a turning point. Its powerful character prompted the team to exclude nearly 25% of their barrels to maintain the desired precision. This selective process often led to the same plots being excluded, not due to their inferior quality, but due to their excessive expression of riper, heavier characteristics.

Jacquet and his team realized they were regularly excluding certain plots from their blends. To address this, in 2019, they leased out three hectares of their Corton-Charlemagne vineyards to Domaine de la Romanée-Conti, shifting their focus to a smaller area. This downsizing allowed Bonneau du Martray to intensify their efforts in farming and winemaking, resulting in more precise and careful practices – particularly in more extreme vintages. It also resulted in additional space for ageing wine in bottle. While DRC are now releasing their Corton and Corton-Charlemagne, Jacquet has reduced his wine sales to négoces and, in good vintages like 2022, he successfully managed to blend all his plots.

Understanding Corton-Charlemagne

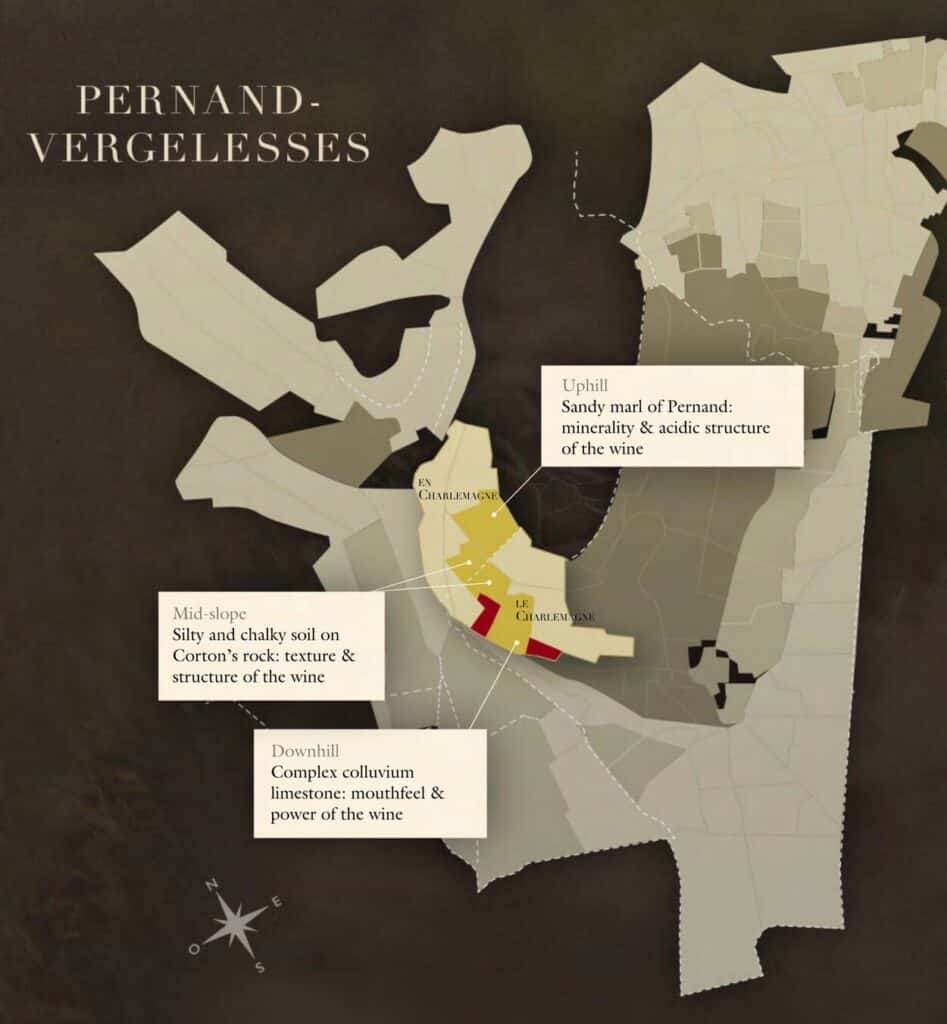

Domaine Bonneau du Martray is located in Pernand-Vergelesses, a vital component of the Corton-Charlemagne appellation. It lies on the southwestern and western slopes of the Corton hill, which comprises three grand crus: Corton, Corton-Charlemagne, and Le Charlemagne, spanning a total of 160 hectares. Over the decades, concerns have been raised by critics and wine experts about the size of this grand cru area, with some suggesting a reclassification of certain parts to premier cru status. The domaine has holdings in the historical heart of Corton-Charlemagne – i.e. En Charlemagne and Le Charlemagne. Recognizing that the vast 71.88 hectare expanse of varying elevations and expositions under the Corton-Charlemagne banner does not adequately represent the true essence of terroir, the domaine decided to leave the appellation in 2021.

Their parcels encompass various aspects of the hill, from the upper slopes, down to the base of the hill, capturing a spectrum of soil types and micro-climates. At the upper slopes, which are near the bedrock, a coarse, shallow limestone lends an austere, chiselled character to the wine, reminiscent of mineral shavings. This minerality is a signature of the western blocks, facing the woods with poor soil and no shade. Mid-slope, the terroir shifts. Marl and limestone from Pernand, mingles with clay, adding tension and precision with a bit more body and a textured nuance. As we descend, the lower slopes are enriched with the accumulation of centuries of sediments over a bed of silt, imparting power, opulence, and flesh to the wine. Domaine de la Romanée-Conti has leased land from all of these three sections.

The beauty of the game for Bonneau du Martray lies in blending these diverse elements. Jacquet looks for a balanced power with a lively and tense midpalate and upper palate. Blending allows him to achieve this profile regardless of vintage. The vintage characteristics will always be there, but the blend can be adjusted, for instance using a higher proportion of the riper lower slopes, to account for any imbalances.

The viticultural philosophy

Corton-Charlemagne’s grand cru is unique in Burgundy for its westward orientation. This aspect affords the vines a gentler morning light, shielded from excessive heat by the rising sun behind the slopes. This positioning is advantageous, particularly during the rainy season, allowing for sunshine throughout the day. The sunsets here, often as late as 9:45 p.m. in the summer months, coupled with the cooling influence of the nearby forest and the Pernand-Vergelesses valley winds, create an optimal microclimate. These winds are particularly beneficial, drying the vines post-rain showers and mitigating wind pressure. Despite these favourable conditions, challenges persist. The vineyard experiences water and thermal stress, mildew, and other pressures, albeit less intensely compared to other regions.

Another challenge is the erosion of the hillside with wind and showers causing substantial soil loss. To tackle this, le Bault de la Morinière installed drainage systems for better water management and began experimenting with biodynamic practices. The hope was that these practices could help revitalize the soil and strengthen the vine root systems, setting the stage for a significant shift in cultivation methods. This gradual transition to biodynamics, meticulously planned over ten years, involved various comparative experiments between blocks to evaluate the effectiveness of these methods. Within five years, the advantages of biodynamic practices became apparent, leading to a complete embrace of this approach. The vineyard was officially certified as biodynamic in 2013.

The winemaking

Premature oxidation and sulphur

Between 1995 and 2002, the domaine, like many in the region, grappled with the challenge of premature oxidation (premox). Unlike some others, they managed to overcome this without resorting to pre-oxidation. More recently, they have shifted towards using less sulphur, guided by their tests showing that wines with lower sulphur levels demonstrated more expression and vitality. Jacquet emphasizes the importance of working with the lees more intensively than relying on sulphur. For instance, the débourbage (settling after fermentation) is now gentler to preserve more solids and lees. It seems to be working, with the 2021 vintage only seeing sulphur when bottled.

Élevage in many vessels and bottle ageing

A signature characteristic of the new Bonneau du Martray is its long élevage process in a variety of vessels with 25% new oak. The time between harvest and bottling has been gradually extended, currently reaching up to 24 months. This extended élevage allows the wines to develop more fully, drawing texture and finesse from their prolonged contact with the lees. The wines are powerful, but they require guidance to achieve precision and purity. Jacquet claims that the lees contact allows for the stretching of that power and make it more integrated.

In their cellar, 228L and 320L oak barrels coexist with an array of vessels: sandstone amphorae, Wineglobes, dolia, concrete eggs.. Before 2017, it was only 228L oak barrels. The choice of vessel is closely linked to the characteristics of each plot and vintage, ensuring a tailored approach to each wine’s maturation. The wine spends a year fermenting and another of élevage. After blending, it rests for an additional year in the bottle. Thanks to the extra space in the cellar from leasing three hectares of land to DRC, there is an intention to prolong bottle ageing for future vintages.

The tasting

Heading down to the tasting room, Thibault Jacquet offered us a small vertical, with a blind bottle included in the mix1.

We started with the 2020 vintage, which Jacquet believes it demonstrates the current identity of the domaine after the years of experimentation since 2017. As we said above, whereas 2017 was a great vintage, 2018 was very ripe and heavy and prompted them to make many changes in the vineyard and cellar, even offering land to lease. 2020 marks the first year where all their tinkering came together. ‘2020 to me is a beautiful conversation between the vintage and the modern Bonneau du Martray’, says Jacquet.

| Domaine Bonneau du Martray – Corton-Charlemagne Grand Cru 2020 | |

|---|---|

| Proper rain in winter and spring. Even though there was a heatwave and a light drought in late July, early August, till mid-August, the vines didn’t suffer at all. | |

| Nose: | Reductive nose, it takes a while to switch on. As is opens there is stone fruit, lemon zest and white flowers over notes of vanilla from the oak. |

| Palate: | Beautiful concentration with ripe pear, but then it has this bone of acid that cuts through it. A tension that reminds us of the wines from Sauzet. It makes it feel fresh and lean – chiselled. All accompanied by jasmine and lemon through the midpalate. The oak in the palate is very well integrated and almost imperceptible. There is no noticeable minerality or salinity. |

| Structure: | High electric acid, dry, medium alcohol, medium body. Very long finish. |

| Domaine Bonneau du Martray – Corton-Charlemagne Grand Cru 2018 | |

|---|---|

| Warm vintage. 25% of the blocks from the estate where discarded. | |

| Nose: | A touch riper (ripe peach) and more smokiness from reduction than the 2020. The oak here is also more overt. |

| Palate: | More body, but still very vertical in the end. There’s more viscosity, more density, with a core of ripe peaches and lemon zest. |

| Structure: | High racy acid, dry, medium alcohol, medium body. Long finish. |

| Domaine Bonneau du Martray – Corton-Charlemagne Grand Cru 2009 | |

|---|---|

| Tasted blind. From the le Bault de la Morinière era. We guessed 2009 vintage right. Jacquet says it’s just coming out of its hibernation now. | |

| Nose: | Very aromatic. Without swirling there’s an alluring menthol or eucalyptus note with chamomiles. The stone fruit here is riper than in the 2020 or 2018, much punchier, leaning towards quince. In the background one can also feel some tertiary aromas of hazelnuts. |

| Palate: | Certainly more body and weight here with a structure that does not have the same electric tension or linearity. There is still plenty of fruit, mostly stone fruit and more exotic aromas of lemongrass, followed by very floral tertiary notes of dried summer flowers or chamomile. |

| Structure: | High acid, dry, medium alcohol, full bodied. Very long finish. |

We finished our tasting with their Pinot Noir, which is now referred to as a Corton Grand Cru Le Charlemagne since 2021. The vinification and viticulture have changed as well since 2017. To enhance the fruit profile and reduce the angular tannins of Corton, grapes are now harvested later, with a greater emphasis on extraction, including more pump-overs and fewer punch-downs. The grapes are all carefully hand-destemmed, with a select batch macerated separately in terracotta amphorae for three months. The long infusion provides more perfumed notes, Jacquet claims. Here they still age each block in a range of vessels (amphorae, Wineglobes, stainless steel…), but the new oak percentage is increased to 50%. After 12 months in oak barrels, the wine is blended and spends another year in tanks.

| Domaine Bonneau du Martray – Corton Grand Cru 2017 | |

|---|---|

| Opened 24h before. Made from two blocks out of the fifteen in the estate. Three are planted with Pinot Noir, but one that was planted in 1979 has been uprooted and replanted in 2018 and is still not in use. The team thought that the quality of the rootstock was not good enough. The other two blocks were planted in 1949 and 2007. | |

| Nose: | Very perfumed. Very pretty ripe raspberries and violets. Solar year, but the fruit is cool and still red. The new oak shows well integrated. |

| Palate: | Beautiful concentration and very fresh. After the pure red fruit attack, there is a light touch of sousbois, crushed rocks and pine in the midpalate. The finish reveals spicy notes of oak like clove with a bit of black pepper. |

| Structure: | High acidity, medium silky tannins, medium alcohol, medium body. Very long finish. |